River Information

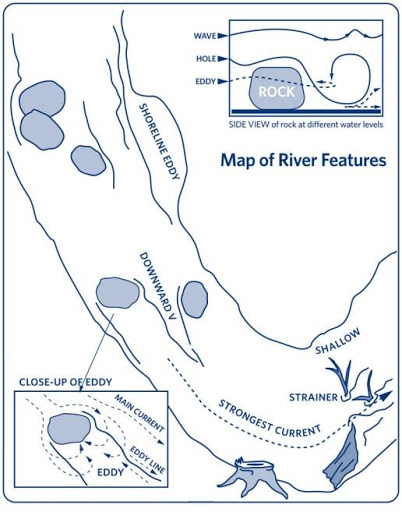

Upstream V’s are formed when water splits around an obstruction. At the top of every upstream V, there is a rock. Downstream V’s are formed where the water flows between two rocks or other obstructions. They indicate a clear, deep water path and point the way to go. An eddy is a relatively slow and calm, upstream current behind an obstruction. Eddies provide stopping spots for paddlers to rest and look downstream. The line between the upstream eddy current and the downstream river current is called the eddy line. As water slips around or over the obstruction, it piles up creating a pillow. When it comes to rivers, “pillows are stuffed with rocks.” A hole or hydraulic is formed when water flows over an obstruction and lands on surface water below, creating a depression. Downstream surface water rushes upstream to fill this void creating a vertical whirlpool effect. With added volume, the water over that obstruction becomes deeper and flushes out the hole becoming a wave. Trees that trap floating objects while allowing water to flow through them are called strainers. Strainers are extremely dangerous (often called “drowning machines”) and should be avoided at all costs. If there is no way to avoid a strainer while swimming after capsizing, swim aggressively towards it, keeping your body on the surface. Pull your body up and over it before your legs get pulled under it.

Upstream V’s are formed when water splits around an obstruction. At the top of every upstream V, there is a rock. Downstream V’s are formed where the water flows between two rocks or other obstructions. They indicate a clear, deep water path and point the way to go. An eddy is a relatively slow and calm, upstream current behind an obstruction. Eddies provide stopping spots for paddlers to rest and look downstream. The line between the upstream eddy current and the downstream river current is called the eddy line. As water slips around or over the obstruction, it piles up creating a pillow. When it comes to rivers, “pillows are stuffed with rocks.” A hole or hydraulic is formed when water flows over an obstruction and lands on surface water below, creating a depression. Downstream surface water rushes upstream to fill this void creating a vertical whirlpool effect. With added volume, the water over that obstruction becomes deeper and flushes out the hole becoming a wave. Trees that trap floating objects while allowing water to flow through them are called strainers. Strainers are extremely dangerous (often called “drowning machines”) and should be avoided at all costs. If there is no way to avoid a strainer while swimming after capsizing, swim aggressively towards it, keeping your body on the surface. Pull your body up and over it before your legs get pulled under it.

Class I: Fast moving water with riffles and small waves. Few obstructions, all obvious and easily missed with little training. Risk to swimmers is slight; self-rescue is easy.

Class II (Novice): Straightforward rapids with wide, clear channels which are evident without scouting. Occasional maneuvering may be required, but rocks and medium-sized waves are easily missed by trained paddlers. Swimmers are seldom injured and group assistance, while helpful, is seldom needed. Rapids that are at the upper end of this difficulty range are designated “Class II+”.

Class III (Intermediate): Rapids with moderate, irregular waves which may be difficult to avoid and which can swamp an open canoe. Complex maneuvers in fast current and good boat control in tight passages or around ledges are often required; large waves or strainers may be present but are easily avoided. Strong eddies and powerful current effects can be found, particularly on large-volume rivers. scouting is advisable for inexperienced parties. Injuries while swimming are rare; self-rescue is usually easy but group assistance may be required to avoid long swims. Rapids that are at the lower or upper end of this difficulty range are designated “Class III-” or “Class III+” respectively.

Class IV (Advanced): Intense, powerful but predictable rapids requiring precise boat handling in turbulent water. Depending on the character of the river, it may feature large, unavoidable waves and holes or constricted passages demanding fast maneuvers under pressure. A fast, reliable eddy turn may be needed to initiate maneuvers, scout rapids, or rest. Rapids may require “must” moves above dangerous hazards. Scouting may be necessary the first time down. Risk of injury to swimmers is moderate to high, and water conditions may make self-rescue difficult. Group assistance for rescue is often essential but requires practiced skills. A strong eskimo roll is highly recommended. Rapids that are at the lower or upper end of this difficulty range are designated “Class IV-” or “Class IV+” respectively.

Class V (Expert): Extremely long, obstructed, or very violent rapids which expose a paddler to added risk. Drops may contain** large, unavoidable waves and holes or steep, congested chutes with complex, demanding routes. Rapids may continue for long distances between pools, demanding a high level of fitness. What eddies exist may be small, turbulent, or difficult to reach. At the high end of the scale, several of these factors may be combined. Scouting is recommended but may be difficult. Swims are dangerous, and rescue is often difficult even for experts. A very reliable eskimo roll, proper equipment, extensive experience, and practiced rescue skills are essential. Because of the large range of difficulty that exists beyond Class IV, Class 5 is an open-ended, multiple-level scale designated by class 5.0, 5.1, 5.2, etc… each of these levels is an order of magnitude more difficult than the last. Example: increasing difficulty from Class 5.0 to Class 5.1 is a similar order of magnitude as increasing from Class IV to Class 5.0.

Class VI (Extreme): These runs have almost never been attempted and often exemplify the extremes of difficulty, unpredictability and danger. The consequences of errors are very severe and rescue may be impossible. For teams of experts only, at favorable water levels, after close personal inspection and taking all precautions. After a Class VI rapids has been run many times, its rating may be changed to an apppropriate Class 5.x rating.

Stop: Potential Hazard Ahead. Wait for “all clear” signal before proceeding, or scout ahead. form a horizontal bar with your outstretched arms. Those seeing the signal should pass it back to others in the party.

Stop: Potential Hazard Ahead. Wait for “all clear” signal before proceeding, or scout ahead. form a horizontal bar with your outstretched arms. Those seeing the signal should pass it back to others in the party.

Help/Emergency: Assist the signaler as quickly as possible. Give three long blasts on a rescue whistle while waving a paddle or throw rope over your head. If a whistle is not available, use the visual signal alone. A whistle is best carried on a lanyard attached to your life vest.

Help/Emergency: Assist the signaler as quickly as possible. Give three long blasts on a rescue whistle while waving a paddle or throw rope over your head. If a whistle is not available, use the visual signal alone. A whistle is best carried on a lanyard attached to your life vest.

All Clear – Come ahead: (in the absence of other directions proceed down the center). Form a vertical bar with your paddle or one arm held high above your head. Paddle blade should be turned flat for maximum visibility. To signal direction or a preferred course through a rapid around obstruction, lower the previously vertical “all clear” by 45 degrees toward the side of the river with the preferred route. Never point toward the obstacle you wish to avoid.

All Clear – Come ahead: (in the absence of other directions proceed down the center). Form a vertical bar with your paddle or one arm held high above your head. Paddle blade should be turned flat for maximum visibility. To signal direction or a preferred course through a rapid around obstruction, lower the previously vertical “all clear” by 45 degrees toward the side of the river with the preferred route. Never point toward the obstacle you wish to avoid.

I’m okay: I’m okay and not hurt. While holding the elbow outward toward the side, repeatedly pat the top of your head.

I’m okay: I’m okay and not hurt. While holding the elbow outward toward the side, repeatedly pat the top of your head.

WORMS is an acronym used to guide the process of scouting or reading a river in order to make good decisions about running rapids. It is an excellent tool that can be used to teach paddlers how to read a river to determine how or even if, it should be run.

Water: Where is the majority of the water flowing? Where is the “V”? Does the main flow go where you want to be at the bottom of the rapid? How strong does the current look?

Water: Where is the majority of the water flowing? Where is the “V”? Does the main flow go where you want to be at the bottom of the rapid? How strong does the current look?

Obstacles: What obstacles are there in this rapid? Rocks? Holes? Strainers? Undercut rocks/walls? Which obstacles are the most crucial to avoid?

Route: What are the route options? If there is more than one line, which line looks most straightforward? Does the main flow of water go through the rapid without going into any of the obstacles? What are the other route options, and do they avoid the significant obstacles? If not, can you make the moves necessary to avoid those obstacles?

Markers and Moves: What are the entrance markers? What are some of the markers in the river that can be used to know where you are in the rapid? What moves will you have to make to avoid obstacles? How confident are you that you will make those moves?

Safety: Can you make the line that you are looking at and what are the consequences of not making your line? Do you want to run the rapid one at a time or mother duck style? Should you have paddlers on shore with throwbags in case someone swims?

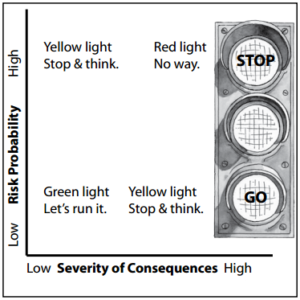

After considering and discussing each of these components, you should be able to make a well-informed decision about the rapid. Use the high/low probability and high/low consequence concepts to help make the decision about whether to run the rapid or not.

Once you have decided to run the rapid, it is important that everyone knows: which line you are running and alternate plans for once you enter the rapid; the obstacles and markers; how you will run the rapid as a group; the safety system you will have in place.

The two primary sources of streamflow data are the USGS and Brookfield Power. Below are links to their sites for gauge data on the various gauges they each maintain. These links will open in a new tab.

Additionally, various online and printed resources are available to learn about the rivers themselves including descriptions of put-in and takeout locations as well as landmarks, rapids, and portages along the waterways. These links will open in a new tab.

Maine Trail Finder

(also great for hiking trails)

(also great for hiking trails)

AMC River Guide: Maine

(printed book)

(printed book)